It was 1968: a year of tumult, turmoil and turbulence.

Start with the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy. And then go on to note that in ’68, the Vietnam War continued raging, race riots continued flaring, and campus unrest continued, well, unresting.

In August, “the whole world is watching” was the battle cry of student protestors who got the crap kicked out of them by Chicago Mayor Richard Daley’s stormtroopers outside the Democratic National Convention.

But it was one month earlier, as a nineteen-year-old student myself, that I was fingerprinted and had my background checked by the FBI. They couldn’t have suspected me of being a draft dodger–that wasn’t until two years later (and a cool story we’ll save for later).

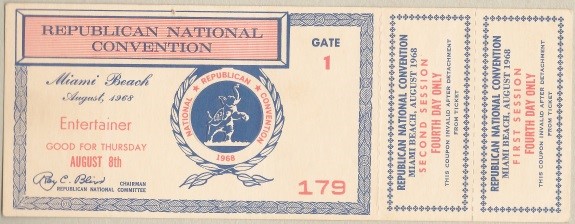

The fingerprinting and background checking were mandatory for me to land a summer job, albeit one that lasted only four days. I had answered an ad and been accepted as an Andy Frain usher for the 1968 Republican National Convention in Miami Beach, Florida. That’s right, an usher. But wait—it turned out to be a groovy gig!

Andy Frain Services was a respected provider of security personnel, particularly to sports and entertainment venues nationwide. Recognized by their signature blue blazers and hat, Frain people were trained in an almost military fashion, with strict codes of conduct.

The blazer and hat I remember. But training? All I recall was something about staying the hell out of the way of Secret Service agents, who we’d know by their lapel pin and a voice that said “Stay the hell out of my way.”

Our job was something I was fairly certain my first two years at Boston University prepared me to handle: take tickets and put some of the 20,000 delegates in their seats, many of whom were already in the bag. At least that’s how they dressed.

The Miami Beach Convention Center was only a half-mile from the apartment building where my folks and younger brother and sister and I had moved to from New York City a year earlier. I could walk there. But in Miami Beach? In August? In an Andy Frain blue blazer? I took the bus.

The Republican National Convention was held August 5-8, with afternoon and evening sessions each day. We were given places to man on a rotating basis. Our assignments might place us in the front lobby, on the convention floor, or in the rear staging area where the speakers sat waiting to step to the podium and deliver their speeches.

On Convention Day One, I was stationed in the lobby at one of a dozen turnstiles. Each attendee had to present a ticket for that day; the ticket had detachable stubs good for admission to each respective session.

In addition, attendees had credentials identifying them as a “Guest” or a “Delegate.” Only Delegates (including VIPs, with special badges) could get on the floor; Guests were taken to the cheap seats.

And that’s what I did on Day Two, directing the un-Delegates up to the balcony to hear hours of tedious droning from lower-echelon speakers, accompanied by a chorus of murmurs from thousands of indifferent individuals more interested in the party they were going to later than the party they were there to support.

Day Three saw me back on the convention floor. The mood of the crowd was peaking, as nomination speeches were set to be made and delegate votes counted. Soon they would select the men who would carry the banner of the Grand Old Party into the 70s.

When I returned for the evening session, I came through the lobby and noticed a commotion at one of the turnstiles. A well-dressed man and woman were being prevented from going into the hall. As I walked closer, the man’s identity became clearer. I did what I thought was right and interceded.

Excuse me,” I said to the usher at the turnstile, a kid no older than me, “this is Governor John Volpe of Massachusetts. Is there a problem?”

“His wife says she left her ticket at the hotel. I’m not supposed to let anyone in without a ticket.”

“Well you can see she’s got the right ID badge,” I said with sudden confidence. “And I know the governor. I’ll take them to their seats.”

Now, this could never happen today. But there was no Secret Service agent nearby, and the usher wanted no part of the hassle. He let us go.

Walking briskly away from the turnstiles and into the hall, the governor smiled and shook my hand. “I want to thank you, son. My wife really did leave her ticket back at the hotel. How did you know us?”

“I just finished my sophomore year at B.U.,” I explained, “majoring in journalism.” This was true at the time, though I would change to a broadcasting concentration within the same School of Public Communication (SPC, now known as COM). Governor and Mrs. Volpe thanked me again as we reached their assigned seats.

When Richard M. Nixon took office the following January, he named John Volpe Secretary of Transportation. Four years later, he was appointed United States Ambassador to Italy.

In the evening session of Convention Day Four, Nixon was set to accept the Republican Party’s presidential nomination, which he won on the first ballot. His chosen running mate would also address the crowd: the relatively unknown Governor of Maryland, Spiro T. Agnew.

I was given the choice assignment in the staging area, immediately behind the podium and out of sight of the conventioneers. It was a comfortable lounge with red carpet, tables and chairs, and a television monitor feeding one of the national broadcasts.

The evening plodded along with preliminary speeches. I had nothing to do but look busy, which wasn’t easy. Even the Secret Service agents just milled around. Nixon, we heard, was in his hotel and not yet in the hall.

At one point, I turned and found myself face to chest with a large man in a black suit. Looking up slowly, I caught sight of his badge. He was the nominee for Vice President of the United States.

“Good evening, Governor Agnew,” I managed to say, like I’d known him all along.

“Good evening,” he replied, and then glanced around with a worried look, as if waiting for someone to tell him what to say next. But that wasn’t it.

“I’ll be giving the next speech and I need to use a bathroom. Where’s the closest one?”

I pointed to a side corridor. “Right through there, governor.” He thanked me and hastened off to take care of business.

After the election, Spiro Agnew became America’s punchline. He insulted his critics by calling them “nattering nabobs of negativism.” College students and their professors were merely “an effete corps of impudent snobs.”

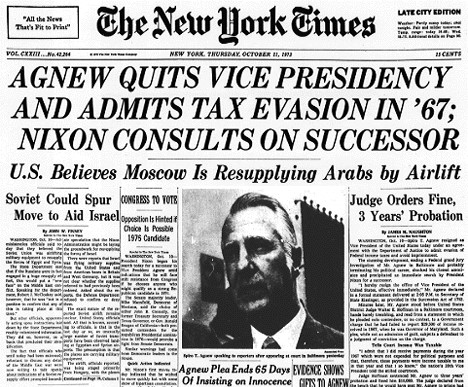

In 1973, early into his second term as V.P., Agnew was charged with having accepted bribes totaling more than $100,000 while holding office as Baltimore county executive, governor of Maryland and vice president. He pleaded no contest to a single charge that he had failed to report $29,500 of income, with the condition that he resign the office of vice president—which he did in October.

All that is a matter of historical record. What is not recorded anywhere else is the one moment in time when a young man in a blue blazer told Spiro T. Agnew where to go—to go.

So funny. How much was the pay?? Probably about $2 an hour?

LikeLike

Don’t remember at all. That sounds about right. Everything in the story happened exactly as I wrote it.

LikeLike